slay the good: morality, drag, and the beautiful lie

a long, slow striptease through the error in ethics. bring singles.

Aug 07, 2025

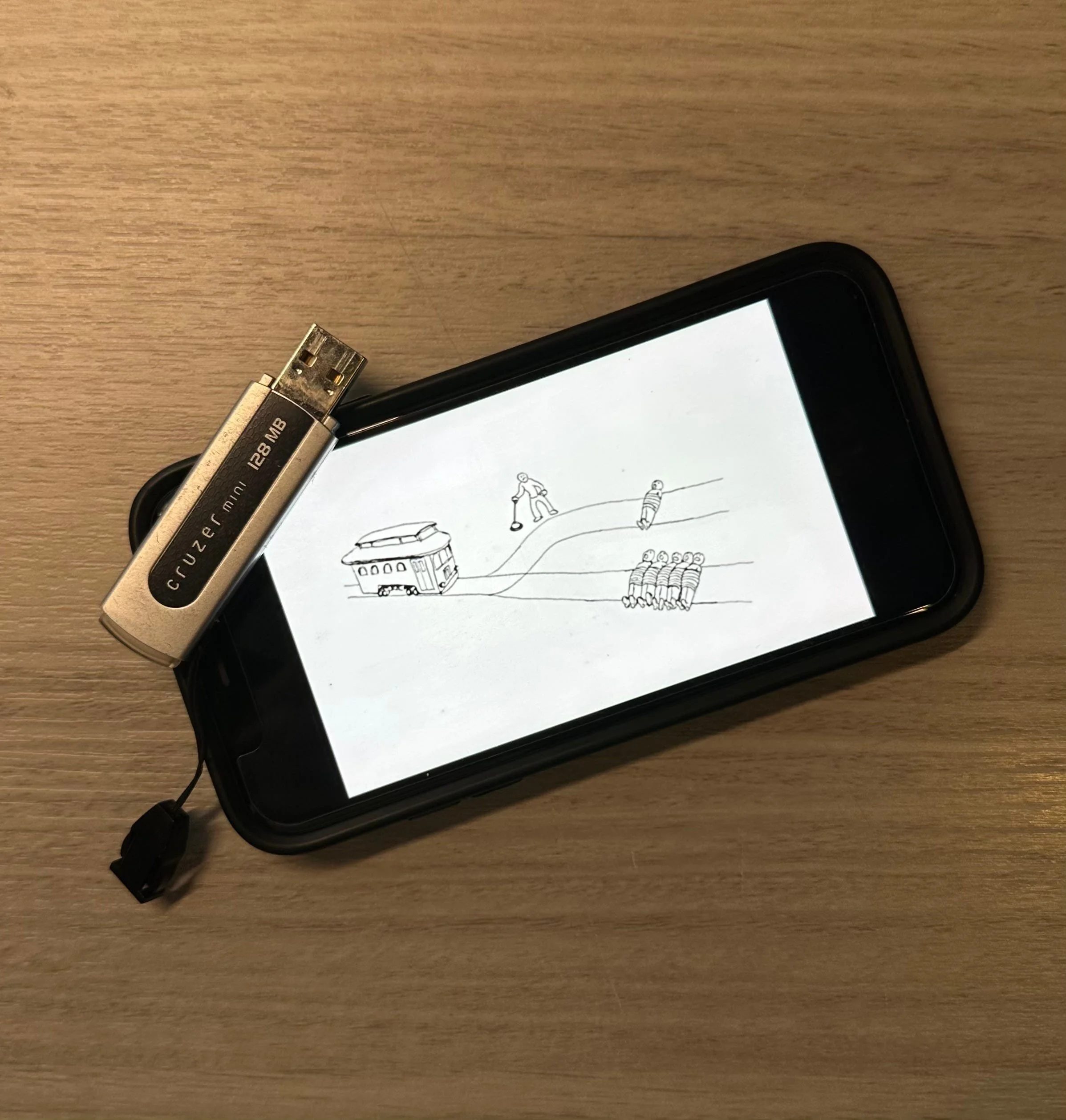

during my recent move, i stumbled upon a fistful of old usb drives and sd cards. i mean old. they were like little digital fossils ranging from 128mb (yes, megabytes) to 128gb. naturally, i had to see what i'd been hoarding. these were time capsules that ranged back to the floppy-disk-transitionary era, tiny archives of a self saved by the kilobyte. like peering through a high-powered telescope, the further back i went, the closer i got to something almost primordial.

and buried in that digital debris? every paper i wrote in undergrad. comparative lit critiques, poetry breakdowns, artsy rambles, deep dives into continental philosophy, and the british analytic stuff that taught me what “nonsense” really meant (i doubled in english & philosophy). among them was my senior philosophy thesis on metaethics, titled, without irony, “aesthetics and error theory: fictional noncognitivism.” (don’t worry. i try my best to hash out those ridiculous words.)

i didn’t want to read it. it felt like listening to a recording of my own voice. just… cringe. so i did what i imagine any retired academic would do these days; i asked ai to summarize it for me. back when i wrote this paper (circa 2011), the idea that i could feed it into a machine and ask it, “hey, does this actually make sense?” would’ve sounded crazy.

but that’s what i did. i asked chatgpt to summarize it, evaluate its quality, and tell me, gently, where i might’ve missed the mark. no prompt, no context. just: what level is this? is it cohesive? and does it actually make a point?

turns out, it did. the bot rated it as “a late-undergraduate philosophy paper, resembling a senior thesis or early grad work,” and gave me some decent critique. a little flattering, sure, but i couldn’t help wondering if it already knew how to stroke my ego based on my prompt history. so i ran it again, incognito, no identity attached.

apparently past me had a few thoughts worth summarizing.

but after reading the ai’s clean summary of something i labored over with zero algorithmic help, i decided to give it a proper human re-read. and honestly? i didn’t mind it. it was my hot take on morality (well, really, an interpretation of other people’s hot takes with my spin), but it’s a paper whose core ideas i’ve haphazardly repeated at cocktail parties over the years. it was my signature at the bottom of my philosophy degree, my sign off, my mic drop. and it felt like something worth revisiting. especially now, when moral discourse feels louder, messier, and more emotionally fraught than ever.

so i’m reframing that paper here, not as an academic artifact, but hopefully as something digestible and accessible to anyone interested. i want to talk about metaethics again. metaethics isn’t about what’s good and bad. it’s what we mean when we use words like “good” and “bad.” specifically, i want to talk about error theory. make it more than just a philosophy bit i perform for people.

this post is part recap, part remix, part philosophical fanfiction. it's about what moral error theory is, why it matters, and where i thought (and still think) we should take it.

turns out, i still don’t believe in morality. but i do believe in making the lie a little more beautiful.

it’s time to buckle in. hold tight. this turned out to be a longer ride than i expected. but this was fun. seriously. i promise i’m telling the truth.

🌀 the queer truth of error theory

what is error theory? well, when j.l. mackie opens his 1977 book ethics: inventing right and wrong with the line, “there are no objective values,” he doesn’t bury the lede. he launches moral error theory like a bottle rocket: straight up and with no apologies. that single sentence sets off one of the most powerful challenges to the way we talk and think about ethics.

because morality is bold. unflinching. maybe even a little theatrical.

i like to think of error theory as a kind of philosophical drag. it performs the part of moral seriousness, all while knowing the costume doesn’t reveal anything real underneath. it’s not about deception. it’s about expression, and maybe even a little fun. but back to mack. the real fun comes later.

no objective values. ok. mackie believes that when we make moral claims like “stealing is wrong” or “clubbing baby seals is bad,” we’re speaking as if those statements describe some objective property of the act, in the same way we’d describe a material property, like “this apple is red.”

but unlike redness, which we can measure and explain in physical terms, wrongness has no observable trace. it doesn’t emit a wavelength. it doesn't interact with the world the way other properties do. and yet, we use moral language with the same confidence we use to speak about scientific facts. that’s the error.

to understand his point, let’s consider the redness of the apple. when we say the apple is red, we’re referring to a physical phenomenon. the apple’s surface absorbs most wavelengths of visible light and reflects back those in the 620–750 nanometer range, what we perceive as red. that’s a property we can test, verify, measure. it has explanatory power in physics, biology, and perception science.

now, contrast that with a statement like “stealing is wrong.” grammatically, it’s structured the same. it seems to assign a property (wrongness) to an action in the same way redness is assigned to the apple. but where is this wrongness? what light does it reflect? what’s its wavelength? what’s its mechanism?

mackie says: there is none.

this is what he calls the argument from queerness, queer here meaning metaphysically strange, not culturally reclaimed. if objective moral values did exist, they’d be unlike anything else we know. they’d require a special kind of metaphysical entity, an invisible, prescriptive moral force, and a special kind of moral perception, some sixth sense that allows us to detect “badness” floating in the air around human actions. and we simply have no evidence for any of that.

he compares this moral fiction to an older scientific one. phlogiston. in the pre-oxygen era of chemistry, phlogiston was thought to be the substance released during combustion. people believed it was a real thing. it was taught, debated, used to explain fire. then came the discovery of oxygen, and the theory of phlogiston collapsed. it had never existed. so we stopped using the term. we didn't revise it or reinterpret it. we tossed it.

mackie’s claim is that morality is like phlogiston. the whole framework is based on a mistaken assumption, that there are moral facts out there in the world waiting to be discovered. but if there’s no there there, then moral language as we use it is built on a kind of polite fiction. and like phlogiston, once you recognize the fiction, you have a decision to make: keep pretending, or give it up.

that’s the queerness: we speak as if “badness” is out there in the world, verifiable, external, authoritative, when in fact, it’s not. it’s not like redness. it’s not like mass or temperature or velocity. it’s not a thing you can isolate under a microscope or verify in a lab. but we treat it as though it is, and that makes our moral discourse feel broken (to mackie, me, and few other people, at least).

for mackie, and error theorists in general, this is the crux of the issue. we’ve been misusing our language. our moral judgments are attempts to describe something that doesn’t exist, and thus, those judgments are systematically false. all of them. not just the ones you disagree with politically. all of them. from “murder is wrong” to “charity is good.” error theory doesn’t cherry-pick. it wipes the slate.

of course, most moral language doesn’t originate in science. it draws from religion, culture, myth, tradition, utility, whatever gives a community its narrative of how to live. however noble its source, the language of morality carries the weight of objectivity without having the structure to back it up.

so what do we do with this gaping ethical hole? if all moral claims are false, do we abandon moral talk entirely? retire it like phlogiston and move on?

well, not just yet.

there are other voices in the room. and things are about to get emotional.

😤 emotivism and the 'oomph' problem

if error theory feels like a cold shower, noncognitivism walks in with a shrug and a hot drink. it doesn’t deny the weirdness of moral talk. it just softens the blow.

noncognitivists don’t say that moral claims are false. they say they aren’t the kind of things that can be true or false at all. when i say “stealing is wrong,” i’m not describing an external property like “wrongness” floating around the act of theft. i’m expressing how i feel about stealing. my emotion toward it. it’s more like yelling “boo, stealing!” or “yuck, theft!”

this view is most famously associated with emotivism, a theory developed by philosophers like a.j. ayer and c.l. stevenson, who were part of the logical positivist movement. the positivists were deeply unimpressed by anything that couldn’t be verified empirically, scientifically. if you couldn’t test it in a lab or reduce it to formal logic, they considered it meaningless. not wrong. not untrue. just meaningless.

and so, in their view, moral statements weren’t really statements at all. they were “ejaculations” (their term, not mine, but i still won't pretend it's not funny). these weren’t propositions. they were bursts of affect. like grunts. like sneezes. “boo, murder!” “yay, generosity!” the same expressive (and linguistic) category as “ow!” or “ugh!” or “mmm.” the moral equivalent of waving your arms or making a face. language, yes. but not language that said anything about the world.

that’s a pretty, dare i say, demoralizing view of morality. but it wasn’t meant to be insulting. it was just rigorous. clinical. if “murder is wrong” doesn’t refer to anything observable or testable, then under positivist standards, it doesn’t actually mean anything. it's just emotional flare masquerading as a claim. in other words, moral talk is all performance (just not everyone knows they’re in costume).

but here’s where my man mackie and the error theorists diverge.

while logical positivists dismissed moral language as meaningless, mackie insisted it was meaningful, just false. that distinction matters.

when someone says “stealing is wrong,” they are trying to say something about the world. they’re making a claim. they think they’re stating a fact. that’s what gives moral language its seriousness, its apparent authority, and its real-world consequences.

according to mackie, the intent behind moral language is what makes it meaningful. it’s structured like a proposition. it’s used like one. we treat it like one. the problem is, it refers to something that doesn’t exist.

the structure is there, but the content is missing. it’s like writing letters to santa after you’ve stopped believing in him. the mail gets sent. it just doesn’t land anywhere.

so while the positivists laughed moral talk out of the room for being nonsense, mackie looked it squarely in the eye and said, “i see what you’re trying to do. but sorry. it’s all false.”

which brings us back to oomph.

emotivism, for all its elegance, often feels like it strips morality of its power. if all we’re doing is emoting, if moral speech is just a bunch of us ejaculating, how do we explain its hold over us? why does it matter so much when someone calls an action wrong? why do we feel compelled to justify ourselves? why do we bother arguing at all?

this is the oomph problem. mackie thought that moral language carries a kind of “action-guiding” force, something that pushes people to behave, not just react. richard joyce, a philosopher we’ll meet again later, calls this the “categoricity” of moral claims. they don’t just say i disapprove of x. they say you should disapprove of x, too. always. regardless of how you feel about it.

emotivism struggles with that. if moral claims are just expressive, how do they ever take on the flavor of obligation? where does the oughtness come from? the thou shalt not-ness?

so the plot thickens. because if moral language is neither true nor meaningless, then what is it? why does it feel so serious?

hold that thought.

👯♂️ the doppelgänger problem: error theory’s identity crisis

this is the part of my paper where i bring in some criticism and show that what we’re saying still holds water. it’s writing a philosophy paper 101. really, it’s good arguing 101. you gotta give the other sides a chance.

this section is still a little heady, though, despite my efforts to lighten it up, but it’s my due diligence, and you can skip it if you want. i’m not watching.

tl;dr: this guy charles pigden thinks he can defend error theory from a serious problem, the doppelgänger problem, but i think he’s a poser. he’s too scared to go full-tilt boogey with error theory. there’s a better way to kill your evil twin.

so. moral error theory seems to have its feet planted firmly in the void, but here comes the doppelgänger problem and tries to kick the floor out from underneath it. it’s one of the trickiest little puzzles facing error theorists, and if you don’t slow down, you might miss just how awkward it is.

let’s rewind for a second.

as we’ve seen, error theory claims that all moral judgments, “stealing is wrong,” “charity is good,” “murder is evil,” are false. not just some of them. all of them. why? because they make claims about moral facts that don't exist. so far, so good (relatively speaking).

but here’s the headache: if every moral claim is false, then what about their negations?

if “stealing is wrong” is false, doesn’t that make “it is not the case that stealing is wrong,” true?

and if that’s true, haven’t you just ended up affirming another moral claim? you’re now saying something about the moral status of stealing, just in reverse. but if some moral statements are true (even negated ones), you’re no longer a full-blown error theorist. you’ve wandered into moral realism (which says moral judgments are capable of being objectively true or false, existing independently of human opinion or belief), and that’s the very thing you were trying to avoid.

it’s a clever trap. and it’s a serious one.

pigden recognizes this problem and tries to wiggle out of it with something he calls restricted nihilism. instead of claiming that all moral claims are false, restricted nihilism says that most of them are. or rather, that moral discourse behaves kind of like mythology.

he says error theory doesn’t collapse under the weight of a few accidental truths here and there, just as the myth of zeus doesn’t suddenly become real because someone actually throws a lightning bolt.

to quote pigden: “a myth does not cease to be a myth because it contains a few random truths.”

pigden doesn’t say every negation of a false moral claim is true or morally significant. he just says the existence of some true moral negations doesn’t force error theorists to give up the game, as long as the discourse overall is still systematically in error. his approach is more pragmatic and meta-linguistic than metaphysically realist.

so moral discourse, even if occasionally true by technicality, is still fundamentally false in structure and purpose. that’s his patch.

but restricted nihilism feels like a hedge. an awkward compromise. and a weak use of nietzschean thought, but i’ll get to that. it still treats negated moral claims as if they’re morally significant. which, to me, misses the point.

let’s go back to the example:

“stealing is wrong.” error theory says this is false.

“it is not the case that stealing is wrong.” pigden says this can be true.

but is pigden’s sentence really the same as “stealing is right”?

here’s where we can push back.

“it’s not wrong” and “it’s right” aren’t the same kind of claim. the first is a negation of a moral judgment. the second is a new moral judgment. that’s a big difference.

when we say “stealing is not wrong,” we’re not necessarily endorsing stealing. we’re simply rejecting the idea that it's morally bad. that rejection doesn’t smuggle in a new value claim. it just removes one. like pulling a painting off the wall. it doesn’t mean you’re now endorsing blankness. you’re just leaving the space undecorated.

the negation of a moral statement isn’t automatically another moral statement. it’s not a new piece of moral furniture. it’s an absence. a moral non-position. and once we see it that way, the doppelgänger problem starts to lose its bite.

this distinction is subtle, but it matters. if we accept that negated moral claims don’t carry the same kind of moral weight, then error theory doesn’t collapse into realism. it just shrugs and keeps walking.

so while pigden’s restricted nihilism is clever, and maybe even necessary for error theory to survive in strict logical terms, i think the better move is to reject the assumption that a negated moral claim is still a moral claim.

"it is not wrong" isn’t just “it is right” with a mask on.

it just pulls the rug out and walks away.

🐒 joyce’s jungle: fictionalism and moral evolution

transreal fiction bookshop in edinburgh, emphasis on the transreal

let’s pause. now that i’m revisiting all this, with over a decade separating me from the academic mountain i tried to climb in my early twenties, i feel something i didn’t expect to feel: curiosity. the classroom kind from 13 years ago. though not just about moral theory itself, but about the people behind it.

like richard joyce. back when i was writing my thesis, social media was still in its awkward adolescence. facebook still had "is" in the status update. twitter was basically a group text for philosophy grad students and bands. tiktok didn’t exist. instagram didn’t exist. shit, i barely existed.

but now, all of that has changed. the distance between reader and writer, student and philosopher, has collapsed. and the idea that i could just… reach out to richard joyce? say hello? ask him what he thinks of fictional noncognitivism in 2025? it’s wild.

i don’t get starstruck. i categorically reject the allure of celebrity culture. but if i were to fanboy over anyone, it’d be a philosopher. and a living philosopher? how lucky am i? i could tweet at this guy. i could email him. (and after i hit publish on this post, i swear i will.)

i’ve never done it, probably because i’ve carried some quiet fear that he’d find me out, realize i skimmed half of the myth of morality in a rush to make it to some off-campus lingerie party in 2008. that i wasn’t serious enough. that i didn’t deserve to talk about this stuff. but screw that. i’m serious now. so serious. and honestly? i still think he’s onto something big.

so with genuine admiration, let’s talk about joyce.

when error theory says all moral claims are false, and emotivism says they’re just feelings in drag, joyce offers a third way, a path through the jungle. he calls it fictionalism.

here’s the basic idea: moral claims are false, yes, but they’re also useful. so instead of abandoning them phlogistonically, we treat them like a shared social story. a myth. a kind of group performance that helps hold society together. we say things like “you shouldn’t do that” not because it’s objectively true, but because the fiction of morality still functions. it still works.

why do we do this? because it’s helped us survive.

joyce grounds this theory in evolution. he argues that moral discourse, talking in terms of right and wrong, good and bad, was/has always been adaptive. it helped early humans cooperate. it helped them identify cheaters and freeloaders. it shaped tribal cohesion. the people who moralized well? they reproduced. the people who didn’t? they probably got exiled or stabbed.

but that doesn’t mean morality corresponds to some higher truth. it just means it was strategically valuable. like camouflage. or eyebrows.

so, joyce says, if morality is built on a fiction, that doesn’t mean we need to toss it. just stop believing in it.

he writes, “the fictionalist thinks that the correct answer is: ‘keep using the discourse, but do not believe it.’” it’s like continuing to read novels after you stop believing dragons are real. you can suspend disbelief when needed because the story serves a purpose.

and here’s what i love about joyce: he’s not preachy. he’s clear without being condescending. he doesn’t wrap every idea in linguistic barbed wire. his writing respects the reader while still walking them through complicated territory.

most importantly, he opens doors. even when you think he’s locking them.

for example, while joyce is sympathetic to emotivism, he’s wary of it in its purest form. he wants to preserve a sense of normativity. he doesn’t want moral judgments to feel like grunts or groans. we are not just a tribe of ejaculators. he wants moral talk to still guide behavior, even if it’s fictional.

he proposes a fictionalist version of noncognitivism: we keep talking like our judgments matter, even though deep down, we know they don’t refer to any objective truth. that may sound depressing. but to me, it’s deeply honest. it captures the strange middle space we actually live in, where we feel moral pressure even if we don’t believe in moral facts.

joyce’s jungle is dense, but navigable. and the deeper you go, the more you realize it’s not a trap. it’s a clearing.

he’s the first philosopher i read who made me feel like it was okay to love morality while no longer believing in it. that i could still use this language, not out of fear or tradition, but out of shared recognition. we’re all improvising here. we’re just doing it together.

so yes, i’ll be emailing him. finally say hello. maybe i’ll even include this article. ask him what he thinks of all this. and who knows? maybe that’ll be my next post. a call and response.

but for now, the takeaway is this:

morality may be a fiction. but it’s a functional one. and sometimes, that’s all we need.

🎨 nietzsche: artist of the lie

nietzsche by munch

if you haven’t noticed by now, i like to pick and choose from different philosophers like a kid in a metaphysical candy shop. a little mackie here, a spoonful of joyce there, a sprinkle of noncognitivism for texture and fancy positivist jargon sauce. yes, i’m aware this sometimes does a disservice to the thinkers’ broader projects.

but i’m not here to write secondary-source citations for the sep. i’m here to stitch together something that makes sense in the wake of all this moral void we’ve been wading through. the muck i’ve been trudging through in my personal life. something that’s lived rent-free in my head for a long time without much deeper reflection.

so yes, joyce had eloquent critiques of emotivism, and some excellent thoughts on projectivism (that’s for another time). but right now, i’d like to bring in a new voice. one that's loud, poetic, deeply misunderstood, and occasionally prone to aphorisms that hit like a whimper at the end of the world.

enter friedrich nietzsche.

ah yes, nietzsche. the perennial edgelord of undergrad dorm rooms. the supposed mascot of nihilism and despair. the guy misquoted on instagram under moody selfies of men holding whiskey glasses. but if you actually read nietzsche, not the posthumous garbage edited by his deeply unhinged sister, not the bastardized nazi branding of the will to power, you’ll find someone radically different. someone playful. joyful. liberatory. even hopeful.

people hear “nietzsche” and immediately shout (in the voice of the nihilists in the big lebowski): “but he’s a nihilist! he believes in nothing!”

well. yes. but not like that.

nietzsche does flirt with nihilism. more than dear pigden gives him credit for. he acknowledges the collapse of external meaning, the death of god, the evaporation of traditional moral scaffolding. but he doesn’t live there. he passes through nihilism like a doorway. a clearing. a flash of light before something begins.

it’s literally the big bang of morality. nietzsche isn’t celebrating despair. he’s clearing the rubble so we can rebuild. so we can do what he famously called the revaluation of all values.

here’s the move. once we admit that objective moral truths don’t exist (thank you, mackie), and that we’ve evolved to speak moral fictions because they’re useful (thank you, joyce), nietzsche asks (as do error theorists): now what?

if there’s no divine commandment, no external compass, no moral law etched in the stars, what the hell remains?

answer: us.

you.

the individual becomes the source of value. and that’s where things get exciting.

in the will to power, nietzsche writes, “we have need of lies in order to live.” and he means it. for him, morality, religion, even science, all of it is storytelling. pretty little lies. all of it is myth-making. it’s all a human attempt to shape a world that doesn’t come pre-loaded with meaning.

of course, nietzsche wasn’t the first to propose that lies might be necessary to living. long before zarathustra came down the mountain, plato was floating something similar in the republic. he called it the "noble lie." a myth told to citizens for the sake of social harmony and order.

according to plato, not all truths are fit for public consumption. some lies, when strategically deployed, uphold the very structures that make collective life possible. it's not a stretch to say nietzsche radicalized this, swapping societal order for existential affirmation.

but the impulse is the same: sometimes, lying isn’t a moral failing. it’s a metaphysical survival tactic. where other philosophers might respond to this by wringing their hands or constructing artificial replacements, nietzsche says: this is your moment. get to work.

create. invent. become the artist of your own values.

that’s why he calls the human being the artist. not the believer, not the scholar, but the artist, and the highest type at that. he sees artistry not as aesthetic decoration, but as existential necessity. we must create meaning because there’s no meaning waiting for us to find. and when he says that “existence is only justified as an aesthetic phenomenon,” he’s not being flowery. he’s being literal.

he means if life is absurd, if morality is made up, if truth is partial and fluid and perspectival, then the only thing left to do is compose something beautiful.

you don’t discover meaning. you perform it. like a queen lip-syncing for her life, you strut your truth into being.

this idea connects directly to his earlier work in the birth of tragedy, where he introduces the tension between two aesthetic forces: the apollonian and the dionysian. the apollonian is order, clarity, structure. the dionysian is chaos, intoxication, wild creative energy. the best art, and, by extension, the best life, is a dynamic dance between the two. structure meets abandon. reason meets ecstasy. form meets force.

this is also how nietzsche sees moral creation. it’s not just instinct, and it’s not just reason. it’s both. it’s art. it’s mythic. it’s performance. and it’s deeply personal.

which brings us back to error theory and fictionalism.

mackie tells us that morality isn’t real. joyce tells us we should keep using it anyway, just stop believing in it. nietzsche tells us to make it beautiful. if morality is a fiction, fine, but then let’s make it a compelling one. one that speaks to who we are and who we want to be.

and who are the ones best suited to shape that fiction?

the creators. the artists. the ones who don’t cling to old absolutes but dare to paint new maps.

so cool, in nietzsche’s view, we’re all artists now. not just poets and painters, but anyone who takes on the responsibility of shaping value. of saying, this is how i choose to live. this is what i will care about, even if nothing in the universe commands me to.

the artist doesn’t ask for permission. they don’t beg for cosmic backing. they build meaning like a sculptor builds a face out of stone: creatively, powerfully, and without certainty.

and that? that’s how morality becomes art. not because it's false, but because it's ours.

🎭 fictional noncognitivism: ethics as ethical drag

photo: rochelle brown

when i reread the finale of my 2011 paper, the big synthesis, the grand reveal, i actually laughed. back then, we all secretly (or not so secretly) dreamed of inventing a new -ism. a new school of thought that would ripple out through time, inspiring grad students, irritating professors, and eventually landing us a wikipedia entry. i think i believed, truly, somewhere deep in my senior-year skull, that this paper might birth something that would someday be called ogierian philosophy.

i was twenty-two. my ego was a supernova. and honestly? it’s kind of adorable. if not obviously facepalm embarrassing.

so, while re-reading, when i hit the part where i triumphantly unveil my big invention, “fictional noncognitivism,” i chuckled. it sounds so serious. so capital-p philosophical. like i was going to waltz into the annals of metaethics with a leather jacket and a cigarette. fictional noncognitivism. sexy, right? the kind of phrase you’d imagine whispering across a seminar table, maybe even in bed (or adjoining armchairs).

while the name was and is overambitious, the idea still feels worth revisiting. even now.

because what i was trying to do, in my very sincere, very overstimulated undergrad brain, was build a bridge. a way to combine the clarity of analytic philosophy with the creative impulse of art.

i’d spent five years reading the “greats” (well, some of them), and i’d started to realize that the thinkers who moved me most were the ones who didn’t just argue. they painted with their words. they brushed ideas together that were meant to be read, yes, but they could also just be looked at from afar.

like a rothko in the met. they wrote with precision, but also with flair. like them, i didn’t want to just explain or argue about morality. i wanted to build a vision of it that could feel meaningful even in the absence of truth with a capital t.

and this is where i landed.

fictional noncognitivism.

here’s what i meant, i think, and what i still mean:

we’ve established that moral claims don’t refer to objective facts (error theory), that they’re better understood as expressions of emotion or attitude (emotivism), and that we can still use moral language even if we know it’s false (fictionalism).

so why not marry the two? or is that three? four? this philosophy’s polyamorous. but fictional noncognitivism isn’t just a marriage of convenience. it’s a reimagining of moral discourse as art, not argument.

fictional noncognitivism is the idea that moral statements are expressive and performative, not just in style but in substance, and that we know they’re not tethered to any objective truth. unlike traditional fictionalism, which preserves propositional form for practical use, this view keeps the meaninglessness of emotivism front and center: moral language is emotional theater.

but here’s the twist: the harder we feel, the harder we act. the more passionately we commit to the bit, the more prescriptive our claims can become. not because they’re true, but because we need them to move us. to bind us. to make the void feel choreographed.

some of us know we’re in costume. some don’t. but everyone’s in makeup.

fictional noncognitivism embraces the absurdity and says: yes, we’re acting. and that’s exactly why it works. it’s saying “that’s wrong” not as a scientific claim, but as a performative ritual. as an aesthetic gesture. as ethical drag.

and that drag metaphor still holds up.

like drag, moral discourse is elaborate, stylized, coded, exaggerated, and deeply expressive. it’s not “true” in the empirical sense, but it’s real in the way it moves people. in the way it creates community. in the way it gives people a persona to embody when the one they were handed no longer fits.

we speak in moral language because it helps give shape to our feelings, bind us to others, and tell a story about who we are trying to be. not because we think our moral judgments are hovering in some platonic dimension, guarded by, god forbid, god, waiting to be uncovered. we play roles. we improvise. we commit. and we care deeply about the script, even when we know it’s all make-believe.

that’s the paradox that still haunts and excites me. we can perform something as if it’s true, while fully knowing it isn’t. we can lie together. we can lie beautifully. and we can still use those lies to build better ways of being.

so yes, we are all fictionalists. and noncognitivists. and liars.

but we’re also artists.

and if we have to lie to live, then let’s make the lie worthwhile.

🎤 my conclusion: lie better

i think i’ve beaten the chameleon to death by now

mackie taught me to question everything i thought was obvious.

joyce showed me that even falsehoods can hold us together.

and nietzsche? nietzsche made lying feel like an art form.

that’s a trio i wouldn’t mind taking a road trip with.

mackie’s in the back, pointing out how nothing we see is objectively valuable.

joyce is riding shotgun, calmly suggesting we keep using the map, even if it's fake.

nietzsche’s driving, windows down, blasting wagner and laughing maniacally.

and me? i’m riding bench (in my ‘99 lesabre), scribbling fake directions in glitter pen and calling it a theory.

so yeah, if morality is a lie, let’s lie with conviction. let’s lie like artists. let’s lie like we mean it. let’s lie like the queens we are, in full face on closing night.

thank you for coming with me on this journey if you made it this far. this was fun for me at least. at best, cathartic.

and joyce, if you’re reading this, i promise i’ll finally send that email.

soon.

probably.

maybe.

if i don’t… just pretend i did.

✍️—clark

credits & blame:

special thanks to dr. a. david kline at the university of north florida for holding my hand, indulging my tantrums, and gently redirecting me whenever i veered off course. any errors above are, of course, entirely his fault (philosophically speaking).